Murder in Munich

40 years on, members of the 1972 Irish Olympic squad reflect on one of the most dramatic weeks of their lives.

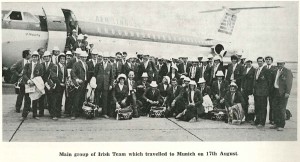

With dreams in their pockets and hope in their hearts, over 7,000 athletes from 121 countries converged on the city of Munich on 26 August 1972, for the opening ceremony of the 20th Olympiad.

But the joy of medal success would soon be shattered by tragic events at 31 Connollystrasse.

In the early hours of 5 September, eight members of ‘Black September’, a Palestinian terrorist commando, scaled the ring-chain fence of the Olympic village, loaded their weapons, readied their grenades and forced their way into Apartment 1 – the block where the Israeli athletes were housed.

They shot and killed two Israeli athletes almost immediately, the blood spatter from their high-velocity weapons spraying the walls of the modest living quarters. Nine others were taken hostage in the violent struggle that ensued.

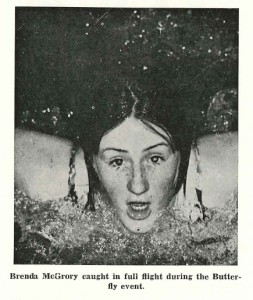

Brenda McGrory, a 16-year-old swimmer from Walkinstown, Dublin was enjoying some down time in Munich city centre when she heard the news. There was an immediate and profound change of atmosphere throughout the Olympic village as she recalls:

“A stillness came over the place afterwards and I do remember there was an eerie feeling. It was a stunned silence really – the fact that people’s lives had been taken. It wasn’t near us but of course we had all the problems in Ireland at the time with our own Troubles so we were conscious of it, even at that age.”

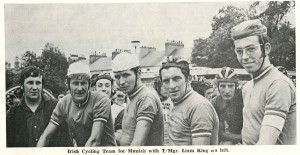

Kieron McQuaid, a 21-year-old cyclist from Ballygall in Dublin first heard that there had been a serious incident at breakfast the next morning. He was due to ride in the road race the following day.

“We went to bed that night and didn’t know if we were competing the following day. So we got up the following morning, got into our gear, went down to the village for breakfast and there were people running around with all sorts of stories. Nobody knew until 10 o’clock that morning that the games had been postponed. There was massive confusion,” he said.

And despite this decision to postpone the games for 34 hours, McQuaid insists the change of schedule had no effect on his performance. Displaying a degree of professional maturity, well beyond his 21 years, he didn’t allow himself to be distracted by events away from competition.

“Our focus wasn’t on running around and enquiring how bad this was. The road race the following day was more on my mind that night than what was going on outside of it. The rest was incidental.”

Frank Murphy, a 22-year-old middle distance runner from Drumcondra, Dublin was attending his second Games. He was closer than most to the scene. His apartment was situated in the block right next to the Israeli team – barely 40 meters away.

“We knew nothing – we heard nothing about it until the next morning and it changed the whole context of the games. People were very upset. It was a complete mess; it was terrible,” he said.

Even German security forces were unaware of the unfolding tragedy, until they were alerted by one of the Israeli athletes who had nimbly leapt to safety from the first floor of the apartment block.

What followed was chaos, confusion and some would argue, one of the most ill-conceived and flawed security operations of modern times. Following a botched rescue attempt, culminating in a shoot-out at the local Fürstenfeldbruck airfield, the final death toll reached 17 – 11 Israelis, five Palestinians and one German police officer.

Frank Murphy was one of the 80,000 people to attend the memorial mass at the Olympic Stadium the next day. A sombre, sober mood descended on the venue. The contrast couldn’t have been greater; the unbridled joy and excitement of the opening ceremony, just days before, had quickly faded into the darkness.

The Games were supposed to showcase a progressive and modern West Germany; a country where all nationalities were welcomed, irrespective of race or creed; a resilient people, who had pulled themselves up by the lederhosen to re-build their broken lives and shattered economy. A new era of hope, prosperity and confidence dawned.

Under the official motto of ‘die heiteren Spiele’ or ‘Happy Games’, the German authorities were keen to portray a friendly and hospitable image to the outside world. There was a conscious decision to avoid the visible presence of heavily-armed guards. Instead, 2,000 un-armed male and female police officers in civilian attire were drafted in, their powder-blue uniforms reflecting the shimmering blue of the Munich skies.

But despite the security criticisms levelled at the German authorities, Frank Murphy believes it was much tighter than Mexico in 1968.

“In Mexico, I could just walk into the village and sign a visitor in. In Munich, the Germans wanted your passport. I had to bring it with me and set up a date for a visitor to come in. You couldn’t just arrive,” he said.

The presence of rigorous security checks is confirmed by McGrory. “You had to have your pass to get in and out. There was an enclosure to check when people were coming and going. You would have thought there was sufficient security but anyone intent on doing something – they always find a way around it.”

It could have been so different, though. Walking into the Olympic Village for the first time, McGrory recalls a happy, relaxed atmosphere. “It was wonderful; from the accommodation to the facilities to the foodhall. I remember thinking, ‘imagine eating goulash in the morning for breakfast’ – little things like that.”

McQuaid says it was everything you would expect it to be. “There were athletes of all shapes and sizes and all colours from around the world in their tracksuits and blazers. I remember noticing people like Mark Spitz – to see people like that eating in the same canteen area where we all ate – it was a wonderful experience and not something that you would ever get again.”

All athletes are unanimous in their support for the decision by International Olympic Committee President, Avery Brundage to continue the games.

“The Games went ahead and rightly so. Otherwise that’s giving into terrorism,” comments Margaret Murphy from Cork. The 28-year-old had already competed in her 200m hurdles and pentathlon events. One of the Israeli athletes had been a fellow competitor.

The Irish athletes came away empty-handed from Munich but all have fond memories of their time there.

“I thought it was a great honour and I was thrilled to pieces to be there,” comments McGrory. “Just to be part of the Olympics – it’s a lot of people’s dreams. The whole experience was wonderful.”

One unfortunate consequence of the 24-hour postponement though, was the fact that the Irish athletes missed the closing ceremony. But security concerns were uppermost in the minds of the Irish management team according to McGrory.

“They had a big dilemma: whether we should attend the closing ceremony in case something else should happen, particularly in view of what was happening in our home country. It would have been nice to be there but it’s one of these things you have to accept.”

McQuaid is a little less forgiving about the decision to stick to the original travel plans.

“To this day, it’s one of the great regrets of my life that I didn’t say – ‘go home I’m staying here and I’ll get home on a bus or a train but I’m not missing the Olympic closing ceremony’. But being that young it would have been a very brave or bold thing to turn around to the Olympic management team and say ‘I’m not going home on your flight’. I’m sorry I didn’t.”

The question of sport and politics is one that’s likely to stay with us for some time to come. McQuaid believes that both are far too closely entwined.

“The Olympics and sport is all about countries representing each other and countries are about borders and ethnic differences within borders. It’s impossible to take politics completely out of sport, much and all as it would be nice to dream of it.”

The 1972 Olympic Games will largely be remembered for tragedy, loss of life and the bungling efforts of German authorities to regain control over a hopeless situation.

But from great tragedy sprang outstanding sporting achievement; a record-breaking seven gold medals for US swimmer Mark Spitz; five medals for 15-year-old female Australian swimmer, Shane Gould and four for tiny Olga Korbutt of the USSR, who captured the hearts of over 900 million television viewers with her daring gymnastic routines.

Looking back through adult eyes, McGrory is philosophical about the events of those fateful days.

“Like children, we’re all very selfish. We don’t think beyond ourselves. When it doesn’t affect you directly, it’s like everything in life, you think about it, you empathise and you move on.”

Appeared in Irish Independent on Monday, 23rd July 2012

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!