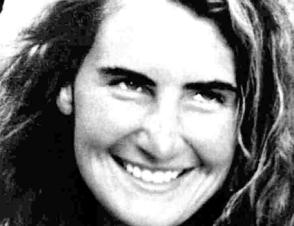

Gone, but not forgotten

On March 26 1993, US citizen Annie McCarrick disappeared from her home in Sandymount. Chief investigators tell Deirdre Cashion why this cold case still haunts them two decades on.

Easter Monday, April 12 1993. Brian McCarthy pulls up a bar stool at the Clontarf Castle Hotel in Dublin’s Northside. He’s just a stone’s throw from the seafront where the locals are enjoying a bright, clear, crisp day along the popular promenade. But dark clouds far away on the horizon threaten the dazzling warmth of the early afternoon sun.

Easter Monday, April 12 1993. Brian McCarthy pulls up a bar stool at the Clontarf Castle Hotel in Dublin’s Northside. He’s just a stone’s throw from the seafront where the locals are enjoying a bright, clear, crisp day along the popular promenade. But dark clouds far away on the horizon threaten the dazzling warmth of the early afternoon sun.

It’s been a busy week for the 35-year-old private investigator from Dublin but life is good. The frothy pint, which sits tantalisingly close, is well deserved but as he settles down to take his first, gratifying sip, the phone rings. It’s the US embassy, a client of his.

A cryptic voice at the other end of the line politely but firmly asks him to make his way to Ballsbridge immediately. There is no explanation offered and none is given, even when prompted.

He reluctantly leaves his pint and quickly makes his way across the swelling Liffey, questions swirling through his head. Little does he know that this decision will determine the course of his life for the next four years.

“The first impression I had when I met John and Nancy in the embassy that day was their sense of loss and despair,” recalls McCarthy. “I spent about two or two and half hours talking to them. I just listened to what they had to say.

“John McCarrick was a typical New Yorker – a big man, very open, very experienced in life, so to speak, as he ran his own grill bar down around Battery Park. After he left the police, he was a special needs teacher and he had a lot of experience of dealing with difficulty in people’s lives. He would have known a lot of street people.

“Nancy McCarrick was completely different. She was a very refined woman. She always struck me as a librarian – and a lovely, lovely woman. I felt really sorry for her as I thought John could express himself quite ably and the sense I got from Nancy was just silence and despair. She was lost.

“I thought, oh my god, what can I do to make her smile again? So I agreed to help them,” he recalls fondly.

The McCarrick’s daughter, Annie had disappeared from her home in Sandymount, Dublin on Friday, March 26. The last confirmed sighting of the tall, striking 26-year-old was made by a former work colleague on the No. 44 bus at approx. 3.30pm. She told a friend she was going to Enniskerry, at the foot of the Wicklow mountains, a favourite haunt of hers which she visited from time to time.

But Annie never turned up that evening to collect her wages from the coffee shop at Baggot Street in Dublin where she worked. She never appeared at a friend’s dinner party the following evening. A bag of groceries, which she had purchased earlier on that Friday morning, lay unpacked on the kitchen table.

McCarthy has always been perplexed by Annie’s decision to head to Enniskerry on that fateful day.

“We looked at the weather forecast. It was a wet day, a damp day. It would have been dark by shortly after 5pm and she was due that Friday evening to collect her wages.

“Now Annie wouldn’t have been particularly well off so her wages would have been important to her. It’s not logical to me that she would go on a bus to Enniskerry, to walk the roads on a dark, damp evening and then to get back into Baggot Street that evening.

“That’s why I’ve always had a nagging doubt – did she even get as far as Enniskerry, and if she did – and this is purely speculation – was she in a hurry and did she accept a lift from someone?”

Born and raised in Long Island, New York, Annie initially moved to Ireland in 1987. She studied at St Patrick’s Training College in Drumcondra and later at the National University of Ireland in Maynooth. She had a quiet, unassuming personality but was spontaneous too and very trusting of the Irish people.

She returned home to the US in 1990 but decided to move back to Ireland in 1993. She was just eight weeks back in the country when she went missing.

By the time that McCarthy was engaged by the McCarrick family to assist in the case, a full-scale investigation involving up to 100 officers was well in train. Led by former assistant garda commissioner, Martin Donnellan, a detective inspector in Donnybrook at the time, the veteran officer knew from the outset that all was not well.

“My first instinct was this doesn’t look right,” he says. “I was supposed to go to a conference down the country the next day but I cancelled it as I knew there was a problem with this girl. We got a very bad feeling and we immediately thought that something serious had happened.”

The investigating team quickly interviewed family and friends to establish Annie’s last movements. They sourced a set of dental records and fingerprints and swabbed for DNA in the apartment that she shared with two female flatmates. Extensive house-to-house enquiries were made by Gardai, armed with an accurate description of her clothing, including a distinctive handmade cardigan with special buttons.

Hundreds of officers and volunteers fanned out across the bleak, uninviting mountains to search for any trace of the young woman.

“We did more digging and searching in water, in drains and gullies,” explains Donnellan. “If you go into that bog and there was a split in the peat, it would be very easy to throw her in, cover her with peat and she would never be found,” he said.

Things were happening very rapidly at this early stage. Donnellan met with the family as a priority.

“Naturally they were demanding answers, and rightly so. They were absolutely distraught because they were so close to her. Annie trusted the Irish implicitly but she met the wrong guy somewhere,” he says.

McCarthy had lost valuable time in the investigation but immediately set about establishing parallel enquiries, looking at different aspects of Annie’s life.

The McCarricks set about printing hundreds of missing person posters and distributing them around the area. A huge media interest built up around the case fuelled by regular Garda press conferences and the offer of a $150,000 reward from the family for information in the case.

“To some degree, you can be hampered by publicity,” according to McCarthy. “Publicity is oxygen and everyone wants publicity for the right reasons. They had a huge amount of people coming out of the woodwork, the so-called psychics and water diviners. There’s a nagging guilt if you don’t chase down those leads, but in chasing them down, there’s a huge amount of time wasted.”

It was after this initial six month period that despair really set in for the McCarricks. With no fresh information emerging, investigators were simply going back over statements already taken, looking at the same thing from different angles.

“Tensions rise, particularly inside the family unit,” according to McCarthy. “John and Nancy were on a rollercoaster of emotions. It came to the point that I think Nancy didn’t want to know anything about leads, she wanted answers. Obviously you want to keep the family briefed but then again, you know by the look on their face, they don’t want another briefing, they want answers. And you don’t have those definitive answers.”

Despite the thousands of man-hours already invested in the case, Gardai were no closer to locating Annie.

“It’s very frustrating,” admits Donnellan. “There was stuff coming in all the time so we were struggling to keep the job sheets done. But it’s very important to keep the officers motivated. You really have to keep driving the team and give praise where it’s due.”

As efforts continued, McCarthy realised that inevitably the McCarricks would be here for a long time. Breaking every rule in the book, he introduced Nancy to his wife, who often took her out and about in an attempt to give her some kind of normal existence.

“From a purely pragmatic point of view, the whole financial thing came into it,” he explains. “The McCarricks had to fund themselves while they were here. I was also funded by them. There came a point in time after four or five months, where I said to John, ‘don’t do this anymore. “And I don’t necessarily want credit for that but I just went, ‘John you can’t afford this’. I’m here anyway – let’s get this done. It became personal to me.”

For the best part of four years, McCarthy continued to chase down every lead, every psychic, every water diviner, and all on his own time. But the case ran into a cul-de-sac. Garda resources were scaled back.

“If you have exhausted all your job sheets and there doesn’t appear to be anything else worth investigating, you have to scale it back,” explains Donnellan. “I felt that the officers in Irishtown worked tremendously hard. There were more enquiries done on it than lots of murder cases. To the best of my knowledge we didn’t leave any stone unturned.”

The McCarricks returned to America and McCarthy has kept a watching brief ever since.

Annie’s case was followed by a series of other unexplained disappearances of young women including Deirdre Jacob, Jo Jo Dullard, Fiona Pender, Fiona Sinnott and Ciara Breen. While Gardai didn’t believe the cases were connected at the time, there seems little doubt now that a serial killer was prowling the highways and byways, searching for his next unsuspecting victim.

With the hindsight of knowledge and developments in another rape case, McCarthy believes this may have unlocked the mystery surrounding Annie’s disappearance.

“I know who the culprit is,” he says with unshakable conviction. “I have no doubt who the culprit is. Can I prove it? No. Does the whole profile of that particular person stack up? Yes it does. It’s the same MO (modus operandi) as is his propensity for violence against women. It’s all there. But can you produce evidence in a court of law? No. Can you accuse him openly for it? No.”

By this time, Nancy McCarrick had come to terms with the fact that Annie was gone forever.

“John never said to me ‘I’m never going to see Annie again’,” according to McCarthy. “He stayed in the angry stage, the ‘someone has to know’ stage. You could call it denial. He never got past that.

“Nancy got past that a lot easier as she had a great deal of faith in prayer and a great deal of faith in her God. She thought, my daughter’s not coming back, it’s God’s will – and I’m not paraphrasing – but I think she took comfort from that and it helped her move on.

Like many parents whose children are lost in tragic circumstances, John and Nancy went their separate ways. The unconditional love for Annie, which underpinned their strong marriage, now drove an irreparable wedge between them. Nancy re-married but that too ended.

“I went over to visit John once, just socially to check on him,” says McCarthy. “Certainly, he had deteriorated by then. It was very apparent to me that his health was suffering and he just went downhill from there.”

He passed away in 2009, a broken man.

Despite his long career and investigation of other high profile murder cases, Annie McCarrick will always stand out as one that got away for Martin Donnellan.

“It would stick very much in my mind,” he says. “It was a real human story. When you meet the parents and see first-hand their distress, you really feel with them.”

Against all odds, McCarthy believes that Annie’s disappearance will be resolved.

“I’m a realist but I’m an optimistic realist if you can understand that. Something, somewhere has to give. Maybe not with Annie specifically but maybe with one of the other girls that will lead back to Annie.

“Let’s say it takes another 10 or 15 years – that will be 35 years since Annie went missing. There’ll be a small ceremony perhaps with a priest at the graveside but who else will be involved and who will be left? Who will care?”

Anyone with information on the Annie McCarrick case should contact Gardai in confidence on freephone 1800 666 111.

Other high profile, unsolved disappearances

- Deirdre Jacob (28) vanished in broad daylight on July 28 1998, while walking near her home in Newbridge, Co. Kildare.

- Fiona Sinnott (20) has been missing from her home in Bridgetown, Co. Wexford since February 9, 1998.

- Ciara Breen (18) disappeared from her home in Dundalk, Co Louth in the early hours of February 13, 1997.

- Fiona Pender (25) was last seen at her flat at Church Street, Tullamore at 6am on August 23 1996. She was seven months pregnant at the time.

- Josephine (Jo Jo) Dullard went missing some time after 11.30pm on November 9, 1995 while hitching a lift from Moone to her home in Callan, Co. Kilkenny.

This article appeared in ‘Weekend’ magazine on March 23, 2013.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!